I didn’t know a lot about civic tech when I joined Truss in 2018, but I had heard about the early impact of two new teams in the federal government, the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) and 18F (named after their HQ at 1800 F Street). I was extraordinarily lucky that those early folks at USDS and 18F were ending their terms as feds right around the time I tried to get into civic tech, and a lot of us ended up at Truss together. It was an incredible learning experience, and strengthened my resolve that I wanted to do more.

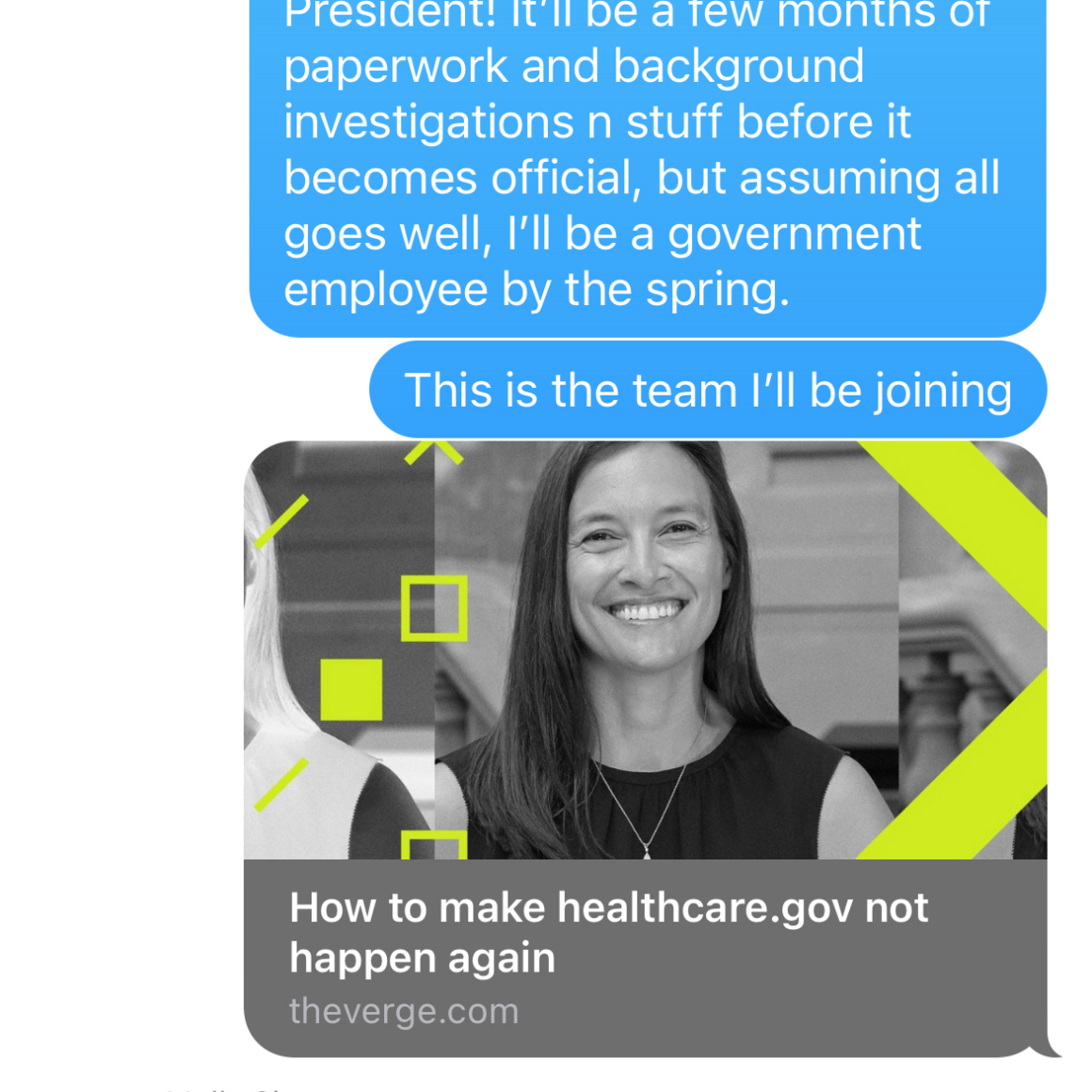

Five years, several projects, and a lot of lessons later, I decided to apply at USDS. I never thought I’d make it through, but I wanted to work on bigger, more impactful projects for the public. USDS has a notoriously tough recruiting process and word on the street was that they only accepted around 2% of their applicants. I tried anyway, got in touch with a member of their talent team at a job fair (Hi, Terrance!), and was off to the races.

Welcome to the White House

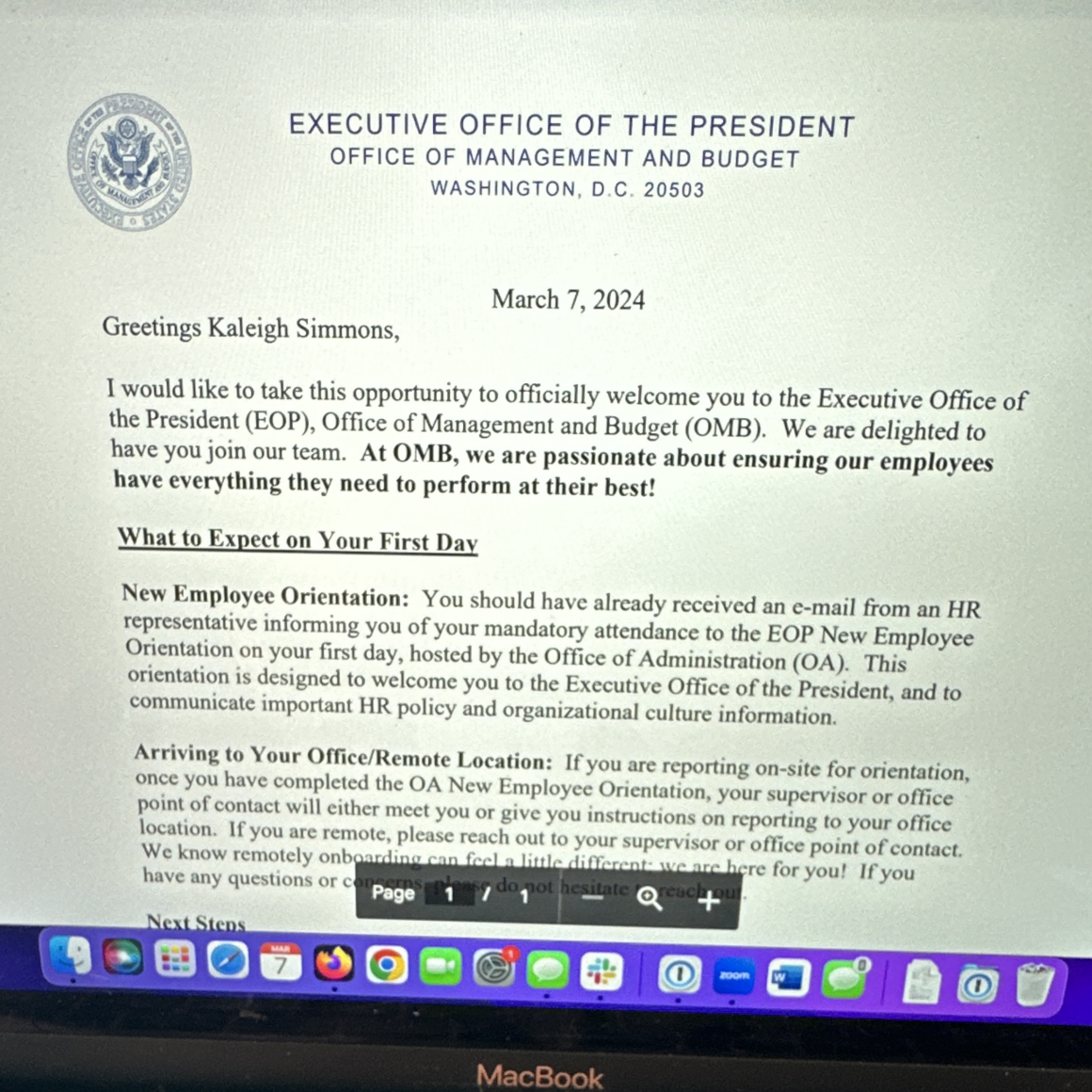

I got my offer from USDS just before Christmas in 2023, and started on March 11th, the day before my birthday. I logged onto my orientation at 7am local time and took the oath of office from my desk in Chicago, IL. I’ll never forget how surreal it felt to hear someone say, “Welcome to the White House.” It never stopped feeling that way.

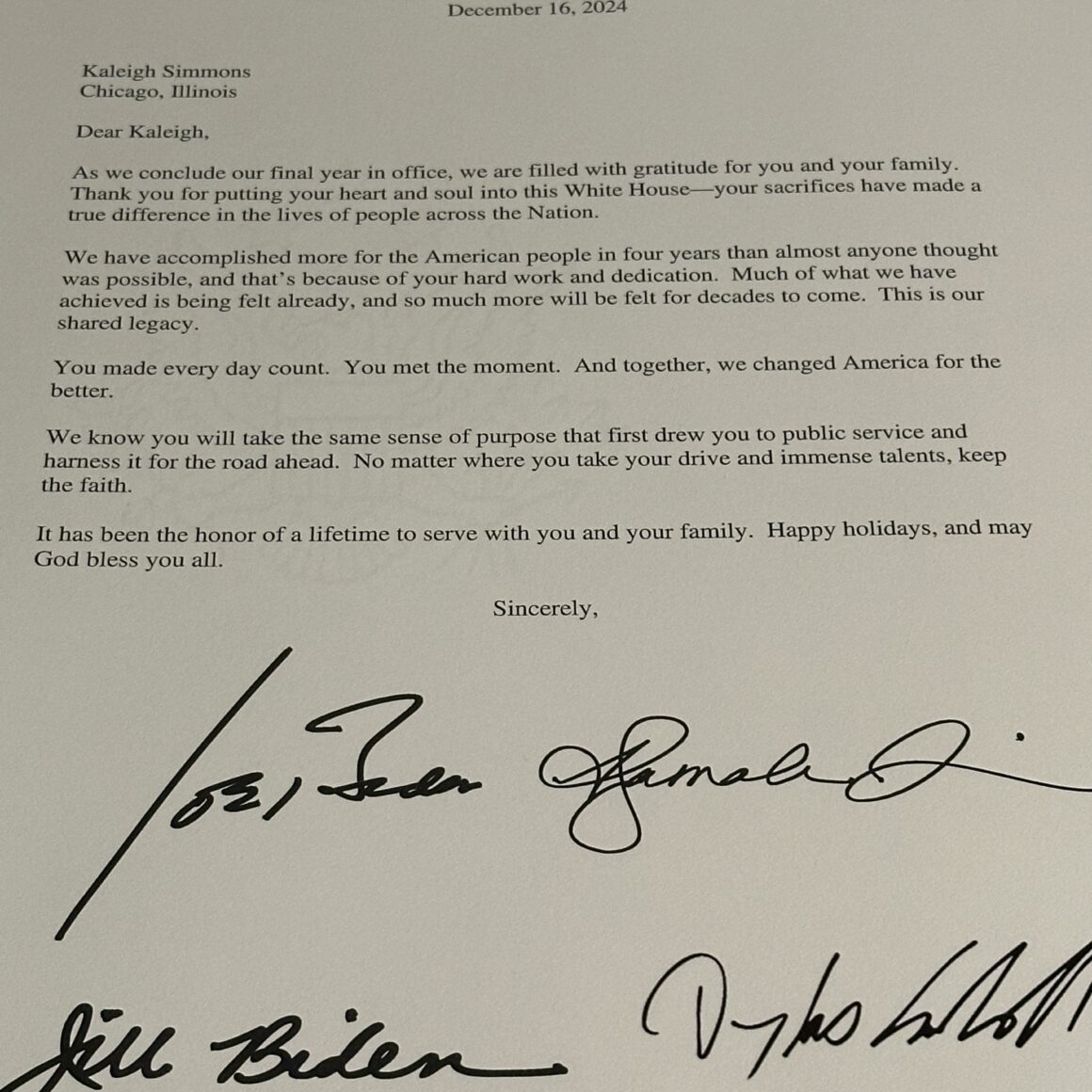

The invitations to meet Olympians, White House Christmas cards, and signed thank you letters from the President and VP… every single one was a reminder of how special my job was and how incredible of an honor it was to get to work for the American people, and in this place.

The agency that touches every American

After a few weeks, I landed on the team that I’d stay on for my USDS entire tenure: Social Security (SSA). I didn’t have a personal connection to the work, but I felt compelled by the fact that SSA is one of the only agencies that touches every single American, so I decided to take my new-person energy and channel it into what I assumed would be the hardest work I’d ever do.

I was not wrong about that. But it was even harder than I anticipated.

What I didn’t realize in my five years as a contractor at Truss, was that even though that work was difficult, the road had largely been paved. By the time a contract is awarded, people in the agency are committed to the work, and there’s a path forward to deliver. USDS projects like the one we were leading at SSA were far upstream from that. There was no path. There was no agency support (yet). There was no money allocated. They may not have even agreed that there was a problem. It was our job to make the case.

Who knew addresses could be so complex

My first project was a discovery (research) sprint focused on why so many SSA customers were calling agents at the 1-800 number to change their address when there were allegedly several other self-service options available. It may seem like a small problem, but SSA was understaffed, struggling to handle the 4M calls they were getting a month, and watching customer wait times ratchet up to 40+ minutes just to talk to an agent. A prior USDS engagement used AI to do a topic analysis on why people were calling, and change of address was mentioned in 20% of all calls during the month they analyzed. So we were off to figure out why.

We had a small cross-functional group from USDS and a dozen folks across several components at SSA. We met daily for a month, analyzing data together, talking with frontline staff, reading policy and process documentation, reviewing customer feedback across all SSA channels, and creating service blueprints of each customer journey.

There were a couple big findings from the work: 1. The interactive voice response (IVR) system only worked for a very small percentage of people, which meant that the overwhelming percentage of folks who attempted to use this self-service path were funneled back to an agent anyway. 2. There were millions of SSI customers with mySSA (SSA online system) accounts who could not use the system to change their address, couldn’t use IVR, and were only allowed to change their address with an agent over the phone.

We presented the discovery findings and our recommendations in one of Commissioner O’Malley’s Security Stat meetings and got support to keep going and figure out what we could fix.

We attempted to make some changes to the IVR script and authentication flow, but for a number of different reasons, including a pending phone vendor switch, didn’t make much progress there. We did, however, get some traction when we started poking at support for SSI change of address online. As expected, the issue was far more complex than it appeared, and a simple address change for an SSI recipient involved two teams of people, half a dozen systems, a series of living arrangement questions, and an assessment for a potential benefit change. There were huge backlogs of pending changes waiting to be addressed by already overburdened staff. Each time a new change was layered on top of an already pending change, it made things even more difficult. It was a low priority task for employees that did not need to be this hard, and a simple change that customers should have been able to make on their own. So we dug in, reviewed prior attempts to streamline this process online, and devised an iterative development plan to deliver it in valuable chunks that would slowly start to alleviate both employee and customer burden. We didn’t get to build the solution out ourselves, but I’m confident that we did enough technical discovery and planning that it can be implemented without us.

Government onboarding

As this was wrapping up, the topic of employee and contractor onboarding came up in a Security Stat. It was a pain point all of us at USDS felt personally as it took several months to get SSA PIV cards and laptops, despite already being cleared for White House PIVs and laptops. Contractors and new employees were having similar experiences, so we started another discovery sprint to figure out why bringing new folks into SSA was taking so long and what opportunities there may be to streamline and shorten it.

I was in a supporting role here, mapping out process documentation and bringing it to SSA staff to help us understand where things differed from the process actively in use, where the pain points were, and where things could be better. This was not the first time I’ve done this kind of work with a team not super bought into the process, but it was still difficult. We were met with resistance at almost every turn, from gathering data to brainstorming improvements.

But at the end of it all, they took our biggest recommendation of assigning one person to own the entire onboarding experience from end-to-end and created a new position to lead this work and seek out improvements.

Benefits modernization

Next, our team was asked to support the Benefits Modernization team inside the Office of the CIO. This team of roughly 70 people was somehow simultaneously juggling half a dozen different projects to modernize critical SSA benefit systems. These were enormous efforts, from replacing legacy DOS style green screen systems responsible for benefit claims intake, to consolidating data infrastructure across benefit stacks.

We led a series of deep dive meetings with each team to understand what they were doing, what problems they were trying to solve, what they were struggling with, and where we might be able to help.

At the end of these sessions, I led our USDS team in a series of synthesis and prioritization exercises to surface what we understood to be the biggest problems facing the team and their customers (which were primarily SSA employees), as well as where we thought would be the highest value places for us to potentially plug in.

Meeting my idols

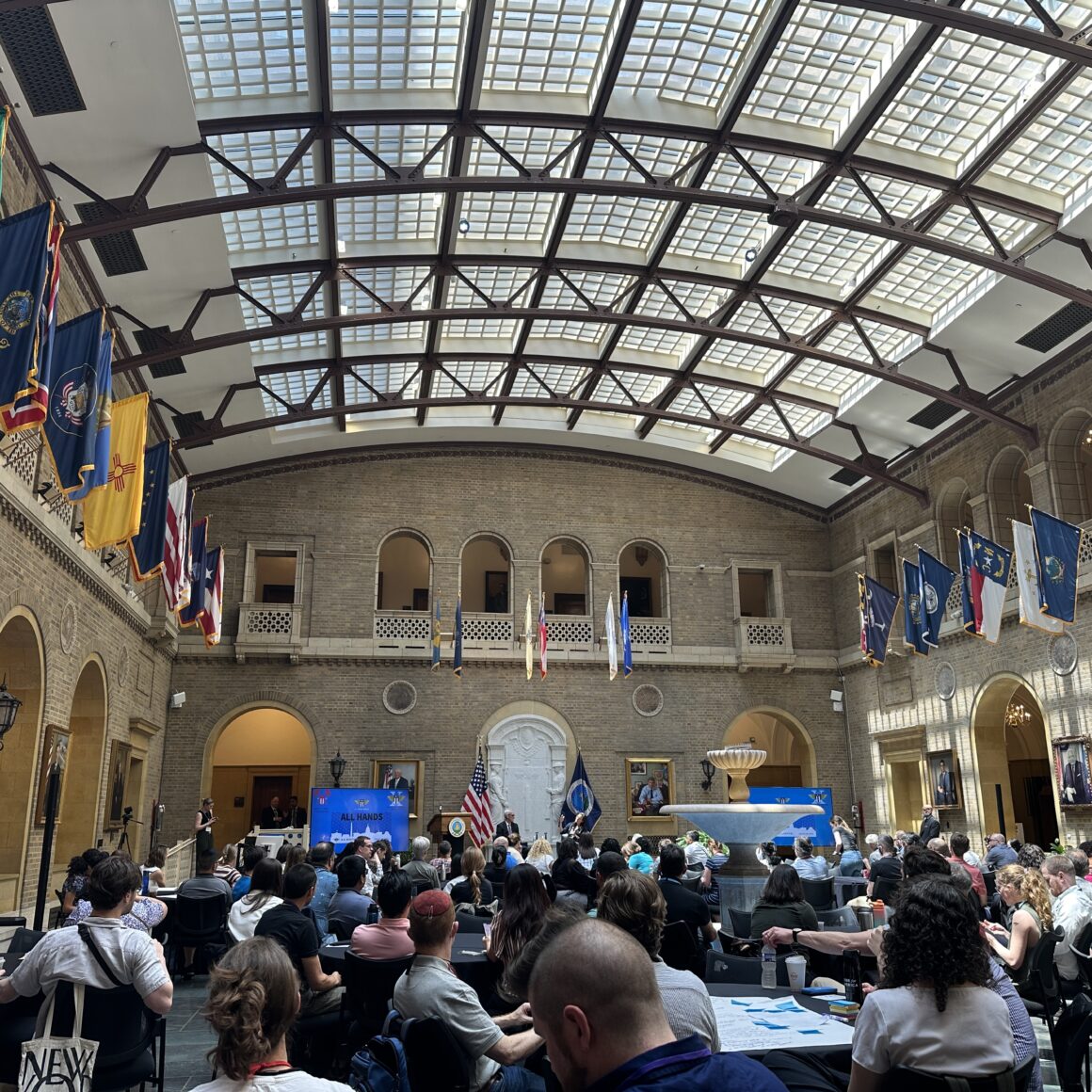

In the middle of this work, USDS had their first-ever full-team All Hands Meeting in DC. It was over 100 degrees the entire week, but it was one of the best weeks in my professional career.

This was the first time I had gotten a chance to meet my SSA and design teammates in person, and the first time I got to enter the White House campus as an employee. I’ll never forget what it felt like to wander through the Eisenhower Executive Office Building. I kept passing members of the Secret Service thinking, “Oh my gosh, they’re going to tackle me any second and drag me out of here,” and instead getting a gentle smile and a nod as they kept on their way. I stood on the Navy Steps and looked across the parking lot to the entrance of the West Wing, just in awe that I was allowed to be there at all. Even though I now live in Chicago, I grew up in a tiny rural upstate NY town of 5,000 people with two blue collar parents. To think that my career took me to the most powerful office in the country was a constant “pinch me” moment. I never took it for granted.

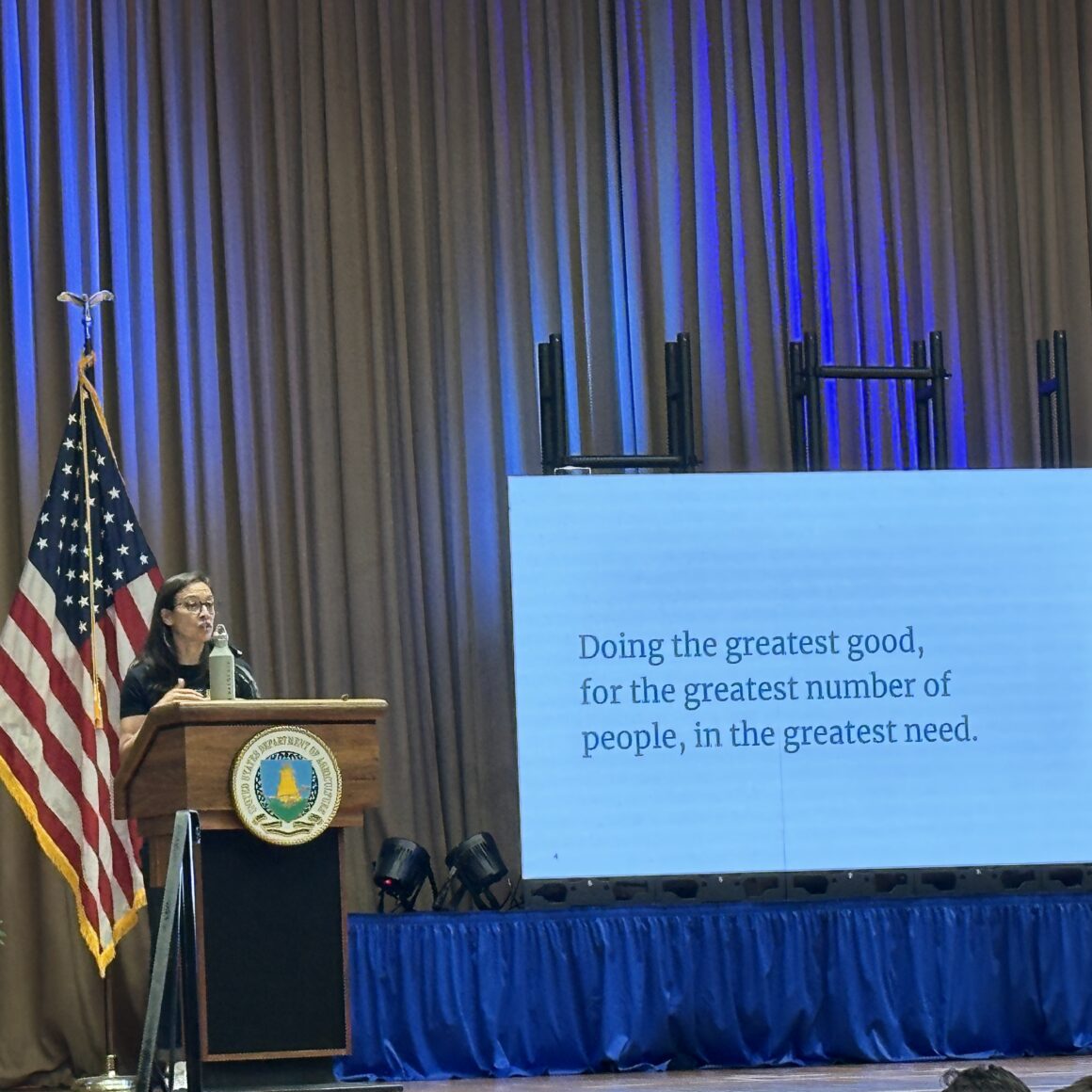

Throughout the week, I got to hear from civic tech legends like Todd Park and Megan Smith, and incredible government leaders like Shalanda Young and Denis McDonough. But most importantly, I got to know dozens of my colleagues and the cool work they were doing across the country. I’m still impressed by all the good that can come from 160 highly-skilled people, motivated to help the public.

The people who make it happen

Toward the end of summer, those of us in Chicago got to make our first trip to the heart of SSA’s service delivery: a local field office. Thousands of employees staff over 1,200 offices all across the country, ensuring that the public has support for everything from getting a Social Security card to filing an application for retirement benefits.

It was humbling to see the breadth and depth of their expertise as they served every customer across myriad needs, and also frustrating to see the (literal) dozens of systems they had to navigate just to complete basic tasks. I was exhausted from spending an 8-hour day there, and these folks had to be the face of the agency 40+ hours a week. I left with a renewed resolve to do whatever I could to lessen their load.

Helping grieving families

Among our USDS team, we were still thinking through a project we could take on under the Benefits Modernization effort that would reduce burden for the public but also SSA employees. We kept circling around the benefit claims process, and the ideas a small design team at SSA had to build out a Universal Benefit Application (UBA) for the public. We knew there were public and employee-facing issues with online claims today, but more than that, we knew there was one type of benefit that didn’t have an online application at all yet: Survivors. No online application meant 100% of claims had to go through frontline staff. No online application also meant that widow(er)s, children, and dependent parents had to navigate a maze of phone calls and in-person appointments during the hardest times in their lives.

The story was clear.

If we could help SSA build out the first-ever online application for survivor benefits, we could reduce burden for phone agents, field office staff, and grieving families. If we could do it under the UBA umbrella, we could build out a scalable infrastructure for this new benefit application system and get something tangible out to the public to test quicker than SSA would be able to if they started with a more complex benefit type like retirement or disability.

We embarked on a discovery sprint to expand our understanding of the problem space, the technical underpinnings of survivor benefits, and the hard numbers around claims and how they were filed. We were confident we could deliver a small MVP that would save SSA millions of dollars while providing the public a smoother path to their entitlements, presented the pitch to the Benefits Modernization team, and started to build.

Alongside subject matter experts from the Benefits Modernization team, policy folks, and SSA’s UX and service designers, we quickly prototyped a significantly slimmed down online application for the Lump Sum Death Payment. By the time I announced my resignation, our engineering team had started building out the front-end. As of my writing this, they had it largely completed.

We had purposefully planned to deliver a front-end first, to have something to show executives as we pushed for support from the other teams we needed to integrate with in order to launch. At least one of those groups was fired last week. Most of the USDS team responsible for pushing the work forward have also resigned or been fired.

It breaks my heart that a project to deliver actual efficiencies is likely on its last legs, and that dedicated civil servants out to solve real problems have been made out to be the enemy. This isn’t how I envisioned my time at USDS going, and this isn’t how I wanted to leave.

But if there’s one thing I’ve learned in my six years in this work, it’s that good people and good ideas always find a way of getting through the noise. This particular work might not make it out, but the people responsible for it will continue to do good elsewhere. For me, I’m turning my sights to what I can impact at the state level, and I’m taking everything I learned in this whirlwind year at USDS with me. Thank you for all of it. Here’s to whatever comes next.